It’s been nearly a month since my last blog, I’m afraid, due to lack of time. This will therefore be a bumper entry featuring two sites and one exhibition in East Sussex, and a slight detour in between.

So today I started by heading over to Eastbourne to take in the Eastbourne Ancestors exhibition. It’s housed in the Pavilion on the Royal Parade on the sea front and is easy to find. There is plenty of parking in the car park for the Redoubt Fortress, which is next door. It’s only a small exhibition and is very much aimed at the layperson. However, what got it on my list of places to visit is that it is an osteoarchaeological exhibition, showcasing the results of a £73,800 Heritage Lottery funded project to analyse the sizeable collection of human skeletal remains recovered from archaeological excavations in the town over the years and held in store by Eastbourne Heritage Service. More than 300 skeletons were analysed using modern techniques to identify the demographics and pathology of the skeletal remains. In addition, in 11 selected cases radiocarbon dating and isotope analysis was carried out to identify when they died, what their diet consisted of and where they originated from.

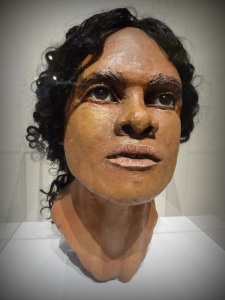

The exhibition features skeletal remains, grave goods and reconstructions including one of so-called Beachy Head Woman, who lived around Eastbourne in the middle Roman period but whose ethnic origins were in sub-Saharan Africa. She lived to be around 22-25, was 4ft 9in – 5ft 1in tall, had an ossified haematoma on her right femur, and ate a lot of fish and vegetables. Apparently further investigation is under way to find out more about her, as indeed are studies of the remainder of the collection within the constraints of the remaining funding.

Following a cappuccino and a scone in the Pavilion cafe I followed the coast road with the thought in my mind that you can’t visit Eastbourne without paying Beachy Head a visit, neither of which I had been to before today. Despite a brief appearance by the sun when I entered the Pavilion a haar had descended by the time I re-emerged and there was a bit of a chill in the air. However, undeterred, I parked up near the Belle Tout lighthouse (now a B&B with a fantastic view) and wandered along the coastal path taking care not to get too close to the edge, unlike the lady pictured. I’m pleased to report that she didn’t fall over the edge and neither did the various other people with smartphones, tablets and cameras doing similar crazy things. The Beachy Head chaplaincy vehicle in the layby and Samaritans sticker on the parking meter were however reminders of the darker side of things at the highest chalk sea cliff in Britain at a maximum of 162 m above sea level.

My next port of call was the Litlington Horse, that is the new one, which I passed quite by chance and noticed out of the corner of my eye. There was previously a chalk horse on Hindover (aka High and Over) Hill (OS grid reference TQ 510 009) which was cut around 1838, perhaps to mark Queen Victoria’s coronation it has been suggested. The present day horse is thought to have been cut as a replacement for the original in 1924/5 and is only around 100m from the first one’s position on the hill. Its present day raised foreleg was apparently a 1983 modification.

I then continued down the road to take in the Long Man of Wilmington on Windover Hill (OS grid reference TQ542034). He’s quite a striking presence in the landscape and I wasn’t surprised to find that he is Europe’s largest representation of the human form. Pleasingly his origins continue to baffle archaeologists and historians alike. Theories include him being the creation of a Mediaeval monk from a nearby priory or that he was the work of the Romans, there being a Roman coin featuring a similar figure, or similarly the Anglo Saxons due to a likeness on some ornaments from that era. The purpose of the Long Man is also debated: could he be a depiction of a warrior or perhaps a fertility symbol? Talking of which, the original artist missed out an important part of the male anatomy and so, it seems, modern day people sometimes feel the need to correct this with paint with varying levels of skill. The current effort is pretty poor, I think.

The archaeology bit

The Long Man of Wilmington inhabits a significant known Neolithic landscape on the South Downs which includes the flint mines at Coombe Hill and the Giant’s Grave and Hunter’s Burgh long barrows and is is certainly possible that he was a part of things back then. There are also Bronze Age barrows in the vicinity and a Bronze Age axe hoard was found nearby so there is more than one prehistoric possibility for his origins.

The Long Man was excavated in 1969 and it was found that the original cut was deeper than it is now thereby making a bolder previous outline. A resistivity survey at that time also revealed that the staves depicted as being held by the Long Man were probably longer than they are currently. Fragments of red tile, previously found scattered within the outline, were analysed by Barry Cunliffe and found to be Roman indicating that the chalk figure at least dates back to the Romano British era although, of course, the Romans may merely have maintained or appropriated the Long Man for their own purposes and his creation may well have been prior to this.

Folklore

Parallels have been drawn with the Cerne Abbas Giant in Dorset and the presence of a Mediaeval monastic house near to both chalk giants has been used over the years to support an ecclesiastical connection. Although the Roman tile fragments mentioned above clearly contradict this, talk of heretical monk occultists must have been a favourite explanation in the past. It was also said that the giant represented Beowulf taking on Grendel. He has been given numerous other identities over the years, all of heroic figures or deities, ranging from Thor to the Prophet Mohammed, as I suppose is only natural given his manly stature and pose. My personal preference however is for him to be a Neolithic fertility symbol and that would seem to be as good an interpretation as any for the time being until such time as new archaeological evidence comes to light to disprove this or otherwise.

Refreshments

Just down the road from the man himself is the Giant’s Rest pub in Wilmington, a nice enough country pub (albeit very close to the A27) which has a good menu and, more importantly, is a stockist of ales from the nearby Long Man Brewery. What other beer to have than the Long Man?

References

http://www.eastbournemuseums.co.uk/ancestors.aspx

http://www.giantsrest.co.uk/index.php

http://www.longmanbrewery.com/our-beers/

http://www.sussexarch.org.uk/saaf/wilmington.html

http://sussexpast.co.uk/properties-to-discover/the-long-man

http://www.wiltshirewhitehorses.org.uk/others.html